By Chris Bergeron/Daily News staff

By Chris Bergeron/Daily News staff

Thu May 03, 2007, 08:22 PM EDT

Framingham –

Psssst, wanna tip? Put a fiver on Roman Mamma in the fifth race at Suffolk Downs.

While you’re at it, check out Joseph Solman’s expressive paintings of subway riders heading to the racetrack. They can be seen at the Danforth Museum of Art.

It is a sure thing, if you’re looking for an artist who found poetry in the daily grind and long-shot dreams.

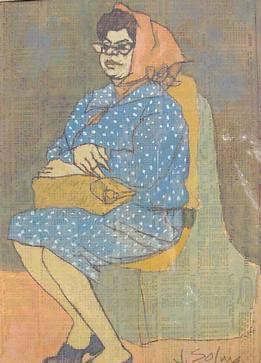

Painting on racing forms and old newspapers, Solman captured weary women with shopping bags and tired feet, a dude wearing polka dot socks and a sad-eyed lady with her kid.

The small but engaging exhibit, “Joseph Solman: Notes from the Underground,” features 13 paintings that will make viewers want to see more work by an artist and part-time bookie who bet on everyday life.

Danforth Registrar Lisa Leavitt organized the exhibit her first which shows Solman’s work for the first time at the Danforth. The show runs through May 20.

“I think these images, painted in the 1960s, speak to a timeless sense of America. Solman gets his sitters’ characters and personalities just right,” she said. “You see the loneliness and alienation of urban America. They’re wonderful images fanciful, colorful and really bring a smile to your face.”

The artist’s son, Paul Solman, will discuss his father’s career and work at 3 p.m. tomorrow, the same day as the Kentucky Derby. Paul Solman serves as business and arts correspondent on “The News Hour” with Jim Lehrer, which airs on WGBH Channel 2 in Boston.

All gallery talks are free to members or with museum admission.

Leavitt said Joseph Solman is “80 (percent) to 90 percent likely” to be at the presentation with his son, who will drive him from New York.

Leavitt came to the Danforth in 2005. The Newton resident earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in art history from the University of Michigan and Columbia University, respectively.

An avid horse player, Solman sketched pictures of other subway riders in pencil as he rode the train to Belmont Park and Aqueduct Race track on Long Island, and Suffolk Downs in East Boston. He colored them at home, often years later. While living in Gloucester, he sketched “The Man with the polka dot socks” while taking the train to Suffolk Downs.

Solman once described the subway “as the greatest art studio of all time,” according to Leavitt.

He often sketched subjects who dozed through the long train rides to the track or watched them as they studied racing forms to determine which horses to bet on, Leavitt said. “He checked out people on the train like you size up a horse at the track,” she said.

Now 98 and living in New York, Solman earned a national reputation as an evocative painter who spent seven decades documenting urban life in his own singular way. Along with Mark Rothko, he co-founded in 1935 The Ten, a group of expressionist painters who worked in the Big Apple in the 1930s.

Born in Russia in 1909, Solman came to the United States at the age of 3 with his family and grew up in New York. He drew as a child, and after high school attended the prestigious National Academy of Design.

Solman is the last surviving member of The Ten, which included Harry Gottlieb, Ilya Bolotowsky and Ben Zion (who was born Benzion Weinman). They showed their work in eight exhibits in the United States and abroad between 1935 and 1939. Solman once explained the group had only nine members so they could bring other artists into their shows.

During that time, Solman also worked with the classic painter Edward Hopper on Reality magazine, and later both vacationed and painted in Gloucester.

Leavitt said Solman unlike Rothko resisted the then-current trend toward abstraction and remained committed to his largely representational but expressive approach.

“Solman was the one who looked at abstractionism and tried to meld it. He recorded the scene but added his own element by flattening his planes,” she said. “He never became an abstractionist. He kept fighting to create a different kind of art.”

In his journal, Solman wrote: “I try to nudge reality toward mystery.”

“To be simple is the most difficult of attainments in art,” he wrote in “Joseph Solman: Seventy Years of Painting” published by Mercury Gallery of Boston.

Danforth Director Katherine French described Solman as a “supreme colorist” and sharp-eyed observer “who interprets the real world.”

“The fact of documenting the world came out of Solman’s working-class sensibility,” she said. “These (paintings) are beautifully realized moments in people’s lives.”

The paintings on display combine watercolor and gouache, so some horses’ racing records can be seen beneath the subway riders’ portraits.

In a 1962 painting titled “Subway Rider,” the records of horses named Roman Mamma and Lolly’s Joy running the seventh race at Lincoln Downs can be partially seen beneath the figure of a rider lost in a private reverie. Other images include “Seated man holding hat,” “Man in olive raincoat” and a “Yuppie” who regards the scene with diffident superiority.

Visitors to the show responded to Solman as a painter who captured moments of unseen beauty amid the press of weary commuters.

“I can almost feel the sway of the car and hear it rumble down the track,” wrote Donna McPherson in a book of comments in the gallery.

Perhaps responding to Solman’s mix of realistic and atmospheric detail, another visitor wrote the train riders are “wonderfully alive.”

“It’s like we’ve seen these people before,” the visitor wrote. “Is this Wonderland, the Red Line?” Another viewer added, “That is me with the handkerchief on my head.”